The narration is conducted on behalf of the author and is based on his biography.

The author compares his life with a fair. A holiday is still alive in his soul, but he is already returning from this fair, and a wall has already begun to grow between his desires and possibilities.

The feelings of the author have become dull, and every day that passes becomes a brick "between" I want "and" I can "." Everything that the author acquired at the fair fits in his heart. Now he just had to take stock and sort out the accumulated treasures-memories.

The author was born in the ancient city of Smolensk. Growing up on the banks of the Dnieper - the eternal border between East and West - Smolensk was the last refuge of people of various nationalities who settled here "in the form of Polish quarters, Latvian streets, Tatar suburbs, German ends and Jewish settlements".

And Smolensk was a raft, and I sailed on this raft among the belongings of my diverse tribesmen through my own childhood.

The author recalls the room where the Vasiliev family lived and his grandmother's friends, a Jew, a Polish and a German, were going to a tea party.

The author recalls his hometown with love, and he is sad that it changes over time. Now Smolensk of his childhood seems to the author as the receptacle of Good, when everyone was ready to help his neighbor.

In the courtyard of the house where the author lived, a huge, centuries-old oak grew, under which little Borya played with his friends. Once his first teacher took the class to this oak and called the tree the oldest resident of the city. Touching the oak, the author felt the "eternally living warmth of History."

Many years later, the author met with young scientists in a city so young that it did not even have a cemetery. Scientists were proud of this and believed that in the age of the scientific and technological revolution, history is not needed - it cannot teach anything. And the author saw only "a city without a cemetery and people without a past."

History ‹...› saves us from the arrogant self-confidence of half-knowledge.

The author recalls the history of Smolensk, inextricably linked with the history of Russia.

Once, the city authorities drained the ancient moat. The boys began to dig out centuries-old deposits of silt and found many different weapons in it - from the Tatar saber to the machine-gun belt.

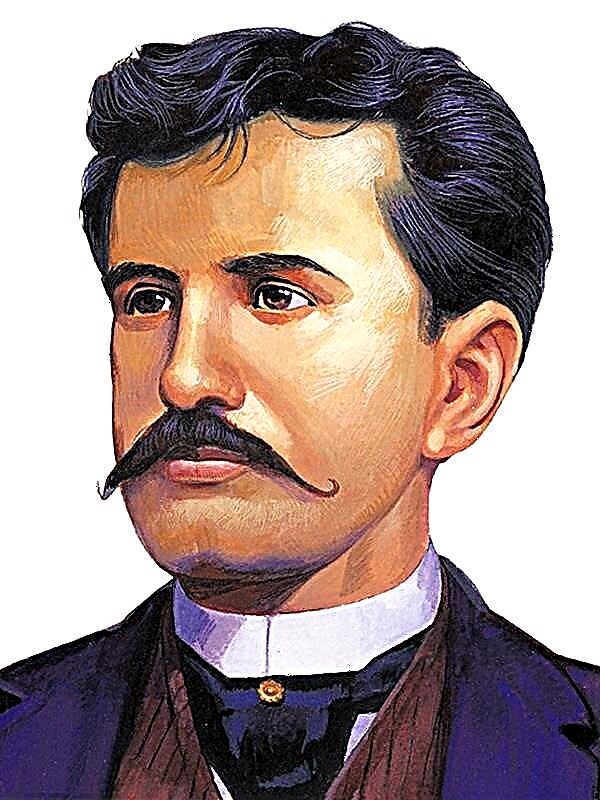

The author’s mother was sick with consumption, and the doctors insisted on an immediate termination of pregnancy, but the woman followed the advice of Dr. Jansen and, contrary to all, gave birth to a son. Sloppy and thin doctor Jansen treated almost half of Smolensk and became for people not only a doctor, but also an adviser.

Holiness requires martyrdom - this is not a theological postulate, but the logic of life.

Residents of Smolensk considered Dr. Jansen a saint, and he died as a saint - he suffocated in a sewer well, saving the children who fell there. At the grave of the doctor, Christians, Muslims, and Jews were on their knees ...

Returning from the fair, the author wonders why a person needs so much energy - both spiritual and physical - with such a short life. Physics of the fifth and sixth grades did not reveal this secret to Boris, and he asked his father. “For work,” he answered, and these words “determined the whole meaning of existence” of the author. He probably became a writer because he believed "in the need for hard, daily, frenzied work."

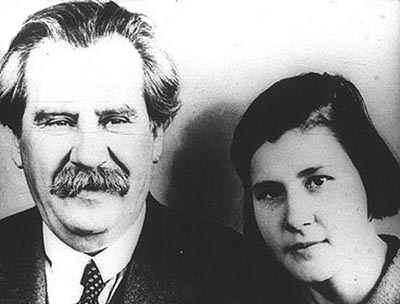

Boris's father was a regular military officer, a red cavalry commander. Despite the years of the war, he did not lose the ability to admire the beautiful - nature, music, literature - and instilled this ability in his son. But he did not discuss the necessity and beauty of labor, but simply worked neatly and modestly.

After all, working without screaming about one's own zeal for one’s labor is as natural as there is no champing.

The author’s family - two children, a mother, grandmother and aunt with a daughter - lived on his father rations and his small salary, so Boris was used to working in a small garden near his home from childhood. He still does not understand how to relax, sitting motionless and looking “into the polished box of someone else's life”, because his parents, even resting, made or repaired something.

The author cannot understand the “thirst for acquisition” that has taken hold of modern man. In his family, "rational asceticism reigned": utensils existed to eat with it, and furniture - to sleep on it, clothes - for warmth, and a house - for life. All his life, the author’s father rode a single “personal transport” - a bicycle.

The only "excess" in the Vasiliev family was books. Because of the profession of his father, the Vasilievs often moved, and the duty of little Boris was to pack books. He knelt in front of a box of books, and it seems to him that he is still kneeling in front of literature.

The author recalls that in Smolensk of his childhood, the most common transport was draft horses. Boris met his horses again ten years later, when he "got out of his last encirclement and ended up in a cavalry regimental school." The horse on which he studied wounded during an air raid, and the squadron commander shot her out of mercy.

In those days, animals were human helpers. The author is unpleasant that now they have turned into pets and become living toys.

The children of old Smolensk did not have more fun than a winter ride on a scrap cab. There were almost no cars in the city. In the early 30s, the headquarters, where the author’s father served, wrote off three old cars. Boris’s father repaired them and created a car-lovers club. Since then, the author spent whole days in the old coach house, where the auto club is located.

In the auto club there was always a barrel of gasoline, and it was lit by a kerosene lamp. Once Borya accidentally crushed the lamp with his foot, and the barrel caught fire. At the risk of his life, his father rolled the barrel out of the barn, where it exploded. No one was hurt, and his father called Boris "hat" - this was his only curse, pronounced with different intonations.

Every summer, the Vasiliev family went out of town to rest. My father could take the car from the club, but he never allowed himself this. But not every father can resist the temptation to ride his son in a company car at that age, "when" you can "and" you can't "are just being formed."

On travel, father and son went on bicycles. Sometimes it seems to the author: the father did not take the car "for the sole purpose: to show that the path between two points is not always useful to connect a merciless line."

Idealizing your parents is much more natural than strictly realistically calculating their shortcomings.

The author recalls the faces of his peers hungry with sunken cheeks. Boris in those post-war times was considered lucky - his father was given a good ration and lunch for the whole family twice a week. Since then, the author never eats on the street - he is afraid to see a hungry look.

Boris Vasiliev compares life with a hunchbacked bridge. To the middle of a man rises, not seeing the future; at the highest point he looks around and takes a breath, and then begins to go down and loses sight of his childhood. On the other side of the man he meets old age, there he is only an uninvited guest.

Old age only has the right to respect when youth needs its experience ...

The author was born at the junction of two eras and saw how yesterday Russia died and tomorrow Russia was born, how the old culture collapsed and a new one was created. He grew up in a "holiday climate" when they think and regret nothing.

The author’s father, grandmother and mother belonged to an old, dying culture. They gave Boris yesterday’s morality, and the street brought up tomorrow’s morality in him. This double effect "created the alloy that Krupp steel could not break through."

His grandmother, a former actress, a frivolous dreamer with a child's soul, especially influenced the upbringing of Boris. She did not pay attention to everyday difficulties and often played the voyage of Christopher Columbus with her grandson, building a ship from a bed and a dining table.

At one time, father Bori was fond of copying paintings. The walls of Vasiliev’s apartment were hung with copies of “Ivan Tsarevich on the Gray Wolf”, “Alyonushki”, “Bogatyrs”. In the evenings, the grandmother chose one of the paintings, composed a fascinating fairy tale, and the picture for the boy seemed to come to life.

My grandmother worked as a ticket dealer in a movie theater. Thanks to this, Borya saw all the news of the then silent movie. He regarded the film as the outline by which he “embroidered” his own story.

Before her death in 1943, a grandmother, who had not recognized anyone for a long time, asked about her grandson, but Boris was at war at that time.

The author writes restraint about mom. This strict woman had a difficult life. During the Civil War, the fighters decided to provide the wife of the red commander Vasilyev with work and food, but military officials "provided" her with work in the infectious barracks, where she contracted smallpox. The disease passed in a mild form, leaving pockmarks on the mother's face - the memory of the Civil War. Boris’s mother survived her father for ten years. She gave her son a lot, but he still can not imagine her young.

Borya studied “disappointingly,” because he often changed schools and was not diligent. He was saved by a good memory and a "fair amount of words." The boy chattered teachers, telling everything that he knew. Prevented Borya learn and his "addiction" to reading. He recited what he read to the homeless children, reveling in his power over them.

In practice, I learned that much later I read from Nietzsche: "Art is a form of domination of people ...".

The Vasilyevs' family often read aloud, but not the adventurous "literature of low bash," which Borya was fond of, but Russian classics. Since childhood, the author has learned that "in addition to the literature that is retold in the basements, there is literature that, figuratively speaking, they read by taking off their hat." He read many historical novels, and literature with history was closely intertwined in his mind. Now, leaving the fair, the author cannot understand how one can not love and not know the native history.

Adventure literature was replaced by a wonderful series of “ZhZZL”, thanks to which Borya learned to bow before the heroes. His father wanted him to do this series. He brought his son a stack of old maps, on which he marked the routes of famous sailors. So the author studied geography, and comprehended military art, drawing topographic maps of the great battles. In the eighth grade, he had already read historical works and was eager to become a historian, but he never became one.

We did not become husbands, fathers, grandfathers. We have become nothing and everything: the earth. Because we became soldiers.

The war became a “charred biography sheet” of Boris Vasiliev.

In the seventh grade, the author studied at a school in Voronezh. There he was very lucky with the teacher of the Russian language and literature, Maria Alexandrovna Moreva. She helped the children create a literary magazine. Together with his best friend, the poet Kolya, the author wrote adventure stories, signing them with the catchy pseudonym “I. Zuyd-Vestov "- Boris at that time" had a penchant for rattling phrases. " Much later, the author gave Kolino the name of the hero of his novel “Not Listed”.

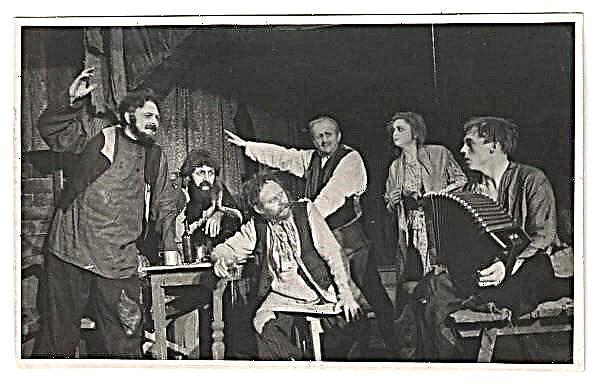

In the same Voronezh school, the author became a member of the drama club. Young actors managed to play only one performance, after which the circle broke up. Then the German teacher invited the children to stage a performance about spies, which was an unexpected success. The famous Voronezh actor saw the play and invited Boris to the rehearsal of Hamlet. From this began the author’s love for the theater.

The author relates himself to a generation that has lost youth.

Youth is the wealth of old age. It can be squandered for pleasure, or it can be put into circulation ...

The author recalls how in the summer of 1940 he, as part of the Komsomol brigade, was harvesting in the Don village. Then he did not suspect that a year later he would be surrounded among the Smolensk forests, and, instead of becoming a youth, he would become a soldier ...

Once, at a plenum of the Union of Cinematographers, the author declared harmful all educational institutions where they teach to write scripts. He now believes that you need to study as a screenwriter only by acquiring your own life experience. Without experience, such training turns into “cultivating geniuses in a flowerbed,” and no creative business trips here will help.

In 1949, when the author worked as a test engineer in the Urals, a group of writers came to their factory. Komsomol members carefully prepared for the meeting, since they considered writers the most insightful people in the world. Now the author knows that the writer is not endowed with supernatural observation. He peers only at himself and sculpts heroes in his own image and likeness.

The author’s father always believed that his son would follow in his footsteps and also become a military man. Boris himself believed in this, and after the war and the end of the military academy he worked for a long time as a tester of wheeled and tracked vehicles. But soon he wrote the play "Tankers", which they agreed to stage in the Central Theater of the Soviet Army. In the wake of success, the author was demobilized in order to "engage in literary activity."

The author’s play was never shown. He tried to write scripts until he realized that drama was not for him. Only one of the plays written by him saw the light. All this difficult time, Boris earned almost nothing, lived on a modest salary of his wife, but did not lose heart.

I always believed in my own dream more frenzied than in reality, and did not sell this faith at the fair, from which I am now returning.

Then the author went to script courses at Glavkino, where they paid a small scholarship. So Boris got into the cinema and met many famous actors and screenwriters. However, it soon became clear that the author was not able to "think cinematically and even write down." All that he wrote was only "bad literature."

The author has lost faith in his abilities. For some time, he made a living by writing texts for film magazines and television shows. He was even first published not as a writer, but as a scriptwriter for KVN.

At this time, the author and his wife traveled extensively throughout the Soviet Union. Once Boris Vasiliev was in the Brest Fortress, where the idea of his novel “Not Listed” arose.

For the first time, a dream has gained ground, concreteness, pathos, and tragedy. The dream began to turn into a thought, excited, instead of lulling, deprived of sleep, disturbed and - angry.

And the author wrote his first story, working as a sailor on a boat, cruising along one of the Volga tributaries. In full accordance with Zuyd-Vestov, the story was titled “Riot on the Ivanovo Boat”, but in the magazine it was called easier - “Ivanov Boat”. The author had to struggle for a long time with the “crackling” style of Zuyd-Vestov.

Boris Vasiliev was offended by doing what he best knows how to write literary works: he was not chosen as a delegate to the congress of filmmakers, and then they defeated his story at the editorial board of the magazine. He simply decided to prove that he was also worth something, and began to write. The author admits that without this defeat, he would not have written his best novels, did not end up in the Yunost magazine, and did not meet Boris Polev.

Ultimately, all the most fragile - for example, love, children, creativity - are slaves of a blind chance. Patterns are valid only for large numbers ...

The father of the author died in 1968, and did not wait for the success of his son. This is a quiet, intelligent man, who lived the rest of his life in a summer house near Moscow, trying not to disturb anyone. He died without ever complaining of a pain that tormented him.

As a writer, Boris Vasiliev was recognized only a year after the death of his father.His writing maturity was expressed in the fact that he finally understood what he should write about.

Since then, there have been many successes; according to the author’s novels, they made films and staged performances. There were many meetings and interesting acquaintances. All this the author is lucky from the fair and regrets that his old dream has not come true - he could not rest a bit, his horses fly very quickly ...

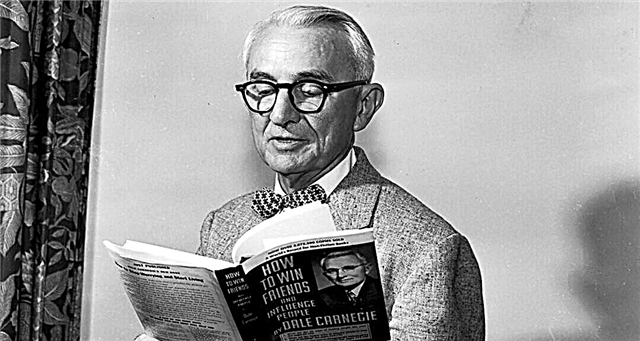

How to make friends

How to make friends